One of the side effects of the booming business of legalized weed is a coming economic shift of no small magnitude. States that have been among the leaders in marijuana cultivation for decades – and whose economies have reaped the rewards despite the illicit nature of it all – may soon be struggling to compete with states where growers can plant and harvest openly and legally.

When every cannabis transaction was conducted under cover, it made sense for most of the harvest to be cultivated where growing conditions were the best, especially if those conditions were found in out of the way places like California’s Emerald Triangle or the mountainous regions of Kentucky and Tennessee. In the emerging marketplace proximity to the customer will be given more and more weight in location decisions, if for no other reason than to keep shipping costs down.

Who Will Come Out On Top?

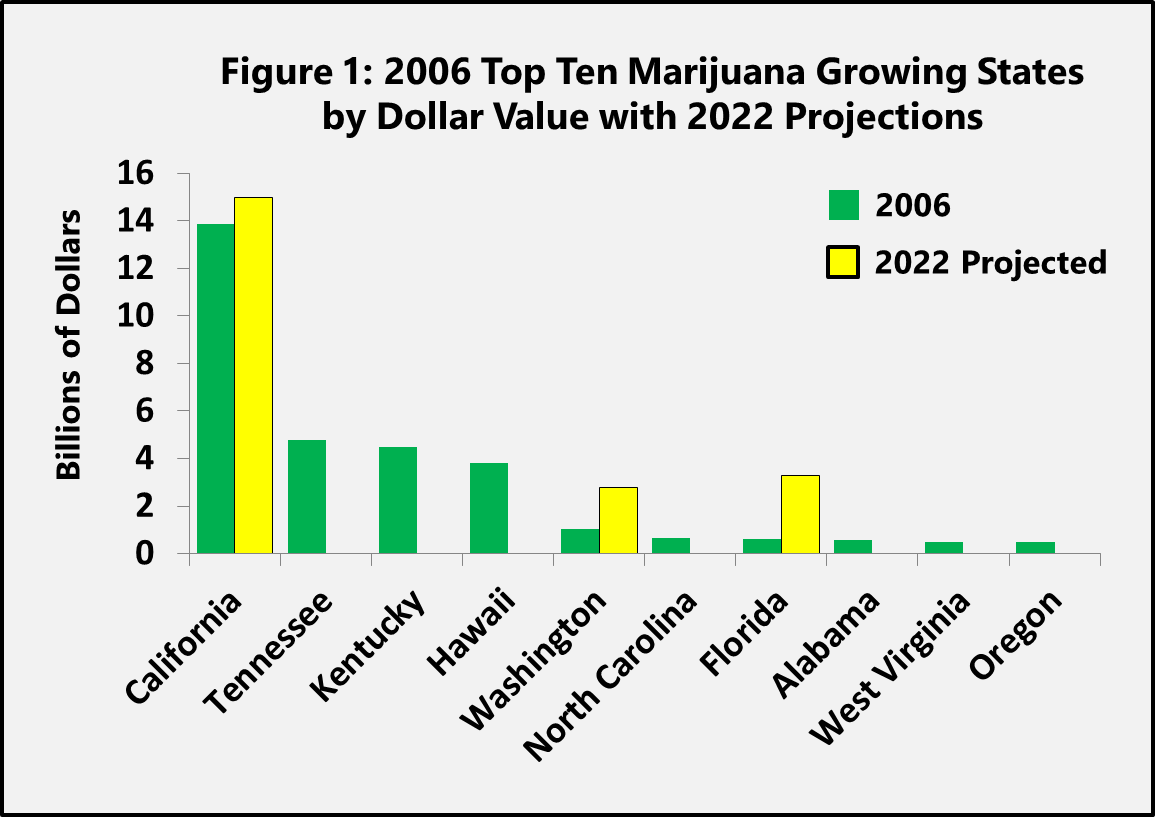

The story of who will win and who will lose is foreshadowed in the way data has been compiled on this topic to date. In doing research for this article I was unable to hunt down any historical state-by-state breakdown of marijuana cultivation published after 2006. (In any case, the numbers would be crude estimates by law enforcement agencies, most likely based on crop seizures.) And today everyone in this industry is so focused on the future that it’s easier to find projections than it is to come up with current statistics. But these two cut-off years arguably make for an interesting comparison in their own right, so let’s take a look at how things were in 2006 and how things are likely to be in 2022. Keep in mind a critical difference in the data, however: the 2006 figures are estimates of illegal weed production. The numbers for 2018 moving forward, however, have been generated by an investment community with a voracious appetite for profits and tax receipts, and so they generally account for legal weed only. In at least some cases those numbers may well exclude a sizable amount of persistent illegal production.

Source: Wikileaf

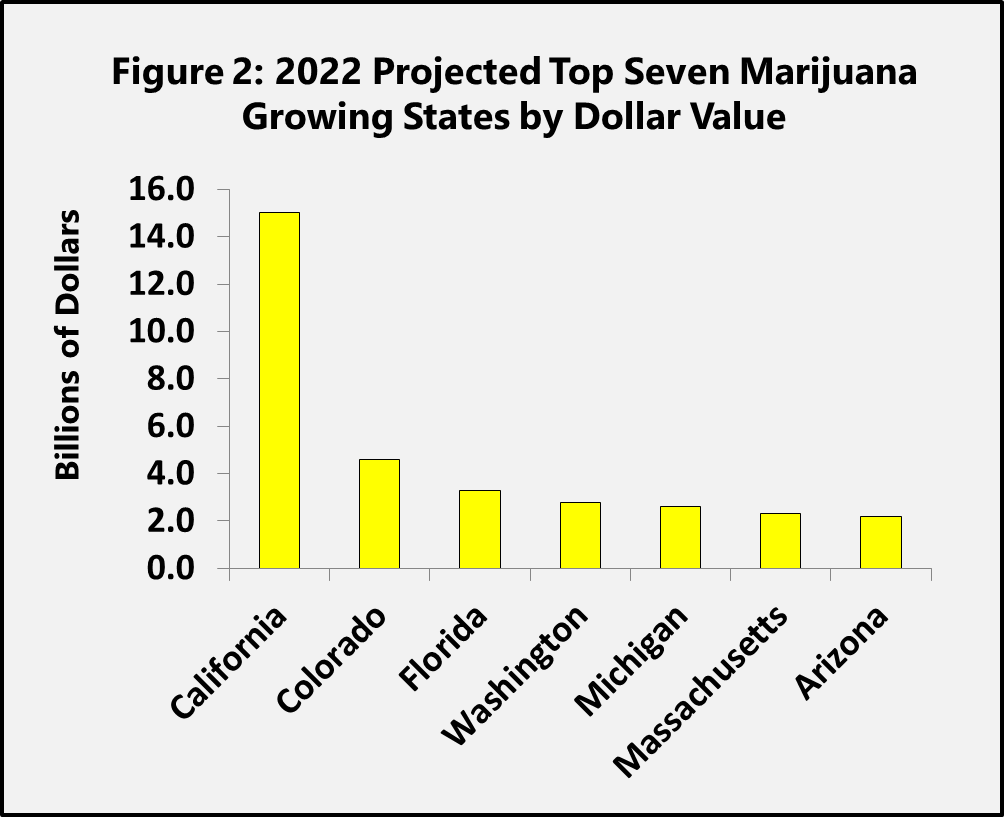

California topped the list of the nation’s marijuana growers in 2006 by a wide margin – because, well, it’s California. The state is credited with output worth $13.8 billion in that year. No surprise, the world’s fifth largest economy (yes, that’s California) is expected to remain the unchallenged leader going forward, with $7.7 billion in legal sales in 2022, more than triple the figure for runner-up Colorado. (See Figures 1 and 2.)

The other leading states in ’06 were on the list for one of three reasons: (1) they were part of a West Coast culture that has long been more open and experimental as well as in possession of good cropland (Hawaii, Washington, Oregon), (2) they were tobacco-producing states that found a profitable and easily adopted alternative once tobacco had lost its luster, or (3) they were named Florida – because, well, it’s Florida, which is not only large and quirky but likewise has good growing conditions.

There’s good news for two of those three groups, in that the West Coast states and Florida are expected to be on the list of highest-value crop producers in 2022 as well. Florida (and a new arrival on the 2022 list, Arizona) both have access to large enough medical marijuana industries that they should be among the top producers even with a recreationally restricted market.

But those tobacco states might not be as lucky. Considered unlikely to legalize even medical use in the near future, they’re likely to see their once lucrative illegal markets siphoned off by states that have people in high places who are more comfortable doing this kind of business.

Kentucky is an interesting case. With a long history as the nation’s dominant hemp producer in the 18th and 19th centuries, when hemp was re-legalized in 2014 not only the farmers but the state government saw the plant’s growing popularity as a great way to transition away from tobacco. Even conservative Senator Mitch McConnell has played a role in encouraging Kentucky hemp production. (Some of the farmers – but not the state government, clearly – saw marijuana as an even better alternative for keeping their lands productive.)

Will the Anti-Cannabis States Get On Board?

Today the state is among the country’s leading growers of both marijuana and hemp, and the latter’s sales are booming. Hemp revenues increased by almost 250% last year, to $57.75 million. But that’s million, with an m, whereas the state’s threatened marijuana production was worth $4.47 billion in 2006. And it’s not likely Kentucky’s marijuana growers can count on the same kind of support from McConnell that benefitted the state’s hemp growers.

Source: Wikileaf

Prior to the 1980s the idea of a city or a state giving incentives to a business to locate operations in their jurisdiction was largely unheard of. Today it’s commonplace – think of the media circus surrounding Amazon’s search for a second headquarters city. If a government ever decided the time was right to give incentives to a legal cannabis company, they would no doubt be pursuing the corporate offices, where most of the jobs are, not the fields themselves.

But the reason this change in government’s perceived role occurred is that states don’t like losing out to one another. Will Kentucky and the other tobacco states ever legalize cannabis for recreational use? The idea faces cultural and political challenges. But those barriers could fall when their governments realize they’re not only foregoing future tax revenues from cannabis, they’re also losing existing economic benefits to other states. There’s a whole body of research in psychology and economics around the idea of “loss aversion” – it’s been demonstrated, for example, that people will work harder to avoid losing $5 than they will to gain $5. When the Kentuckys of the world realize their persistent anti-cannabis attitudes are causing them to lose money they already have, they just may decide that legalizing recreational weed is a lot more cost-effective as a business incentive than handing over baskets full of money.

And that just might keep Kentucky, Tennessee, and Alabama in the Top Ten.